MAAR Panel Report

Child-birth, Child-death, and Poetic Transcendence: Creative Coping through Buddhism in Pre-modern Japan

The following report summarizes the papers presented in the panel of the above title at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Meeting of the American Academy of Religion on March 22, 1991 at Barnard College in New York City. This panel will be held again at the 1991 Annual Meeting of the Association for Asian Studies in New Orleans on Saturday, April 13 in Mardi Gras A/B, 3rd Floor, Marriott Hotel, from 4-6 p.m. The summaries have been provided by the authors themselves.

In his presentation titled “The Five Obstructions” (Gosho, Itsutsu no sawari) as Waka Topos,” Edward Kamens (Yale University) discussed sample poems composed in many periods dealing in various ways with the idea of the “five obstructions” (the five forms of rebirth which, in the “Devadatta” chapter of the Lotus Sutra, Sariputra says women cannot achieve — including the rebirth as Buddhas) and the related idea of gender transformation as prerequisite to Buddhahood as well as the practice of exclusion of women from certain precincts and observances. Using poems that link these ideas and practices in several ways, Kamens argued that the tensions inherent in these ideas and practices are represented not only thematically but also formally in some waka poems, and that the durability of the woman’s handicap/exclusion issue in Buddhist discourse (despite strong refutation) bears a direct (though not simple) relationship to the durability of the related topoi in waka discourse.

Next, Mimi Yiengpruksawan (Yale University) presented her paper entitled “Childbirth and the Commissioning of Artworks at the Court of Taikenmon’in.” Taikenmon’in Fujiwara no Shoshi (1101-1145), a royal consort and woman of uncommon staying power in both history and legend, enjoys the distinction of being the Heian queen about whose parturitions the most seems to be known. Yiengpruksawan investigated contemporary diaries kept by courtiers, some in her direct employ, which show that, with each parturition, thousands of votive sutra transcriptions were commissioned, as well as hundreds of paintings and sculptures of Buddhist deities. In most cases these works were sponsored by the sovereigns Shirakawa and Toba or by their confidantes, with the express purpose that they figure in various rituals directed at insuring an uneventful labor for the temperamental empress.

Barbara Ruch (Columbia University) spoke on “Woman to Woman: Kumano bikuni Proselytizers in Medieval and Early Modern Japan.” Although the prevailing paradigm is that “men are the teachers of religion,” Professor Ruch became aware that this paradigm is seriously skewed when over the years she ran across, in medieval literature and painting, numerous examples of women teachers of the faith. Focusing on the so-called “nuns of Kumano,” the present paper attempts to separate from that catch-all category which includes many types, from shaman to prostitute, those nuns associated with the sacred mountains of Kumano whose proselytizing took the specific form of etoki (painting-recitation) of the Kanshin jukkai mandara. By analyzing the iconography used in these paintings Ruch has attempted to reconstruct the teachings of these nuns. She focuses specifically on what is apparently the first appearance in Japanese hell paintings of gendered hells — and specifically, those depicting tortures and suffering exclusive to women. The paper concludes with an analysis of the etoki nuns’ use of the Heart Sutra, their alteration of the teachings of the Ketsubonkyo (Bowl of Blood Sutra), and their introduction of the Nyoirin Kannon as a savior of women.

William LaFleur (University of Pennsylvania) presented a paper titled “Junctures of Birthing and Dying: The Riverbank of Sai in the Folk-Buddhist Abortion Rituals of Japan,” an exploratory consideration of the history and social role of ritual loci called “Sai no kawara” (the Riverbank of Sai) in Japan. Sites so-named are to be found in various, often geographically distant and desolate looking places. They represent places where the souls of the dead children are imagined to be forced to reside, places where these children long for their parents and try to elicit parental concern for their plight. The mythic origin of this appears to be in Shinto folk practices — as is clear from the evidence, for instance, from Takachiho in central Kyushu. Yet history shows the gradual union of this theme with the Buddhist cult of Jizo — as present in many locations. With the statistical rise in abortion, the use of such sites for visitation by the “parents” of mizuko (aborted children) has expanded greatly. LaFleur’s paper studies the Sai no kawara at the northern tip of Sado in some detail.

Director’s Report

Mary Martin McLaughlin Workshop on Religious Women in the Middle Ages

On February 23, 1991 an invitational workshop of some fifty scholars was held jointly by Barnard College and Columbia University to honor the outstanding work and long career of Mary Martin McLaughlin. Readers of IMJS Reports will remember Mary as an acting member of our December 1989 “Workshop on Women and Buddhism in Pre-Modern Japan” and as our key liaison between scholars of religious women in the medieval Latin West and our team members studying women and Buddhism. The workshop honoring Mary was organized by Caroline Bynum, another active participant from the Latin West side in our Women and Buddhism workshop; also in attendance from the Latin West contingency of our group were Heath Dillard and Suzanne Wemple. Barbara Ruch was kindly invited to represent Japan at the workshop as the lone non-Latin West scholar.

The workshop was extremely stimulating and enriching intellectually and was open and nurturing in spirit — truly a workshop conducted in the spirit of Mary McLaughlin herself. Session one, chaired by Caroline Bynum, centered on “Women and Their Spiritual Advisors” and included presentations by Elizabeth Clark on Jerome and his women associates (4-5th c.), and by Anne Clark on the visions and pronounce-ments of Elizabeth of Schoenau (12th c.) and her brother Ekbert, who ultimately joined her at a Benedictine double monastery and who set down her visions in Latin. Discussion followed on visionary women and the men who recorded their pronouncements or who received their letters (including Catherine of Sienna; Agnes of Montepulciano and Raymond; Margery Kempe; and others). There are striking similarities between some of these women’s visions and personalities and those to be found among Japanese women founders of new religions in 19th-20th century Japan, yet there are also great differences; an area for fruitful exploration.

Session two focused on “Women’s Religious Houses.” Heath Dillard reported on Spanish cartulary evidence (9th c. to 1500) about types of women in religious life (sisters; beata; walled-up women; servant-like nuns, etc.), notarial documents and other materials which include names of nuns, their inheritances, diet, litigations, etc., all of great importance to historians during a period and in an area in which there are no works by or about women but where there were at least 600 communities of women in religious life appearing and disappearing over those centuries. Penny Johnson reported on her detailed computer-assisted analyses of the 640-page Latin Register of Eudes Rigaud (13th c. Normandy), a document rich in anecdotal evidence concerning the lives of religious men and women and which records 596 visitations to monasteries and convents. Eude comments on aspects of life there that deserve praise and those which require censure and penance (failures in chastity, for example). The data reveal that gender is not a major factor in the descriptions of religious life that occur in these communities but that economics is. The comparative poverty, often dire, of nunneries, in contrast to monasteries, is apparent. Discussion centered on the importance of masses and relic ownership to the economic well-being of religious institutions: clearly nuns could not say masses nor did the relics of local women saints attract pilgrims on the impressive scale found with the relics of major male monasteries. There is evidence that in rare and extreme cases nuns may have exchanged sex (with monks?) for food.

The final session on “Women’s Voices” continued closely on themes raised in the opening session. Barbara Newman defended the authenticity of Heloise’s letters to Abelard (12th c.)and discussed issues related to her life and nunhood and to what has been described as her “repression” and her fixation on Abelard. The difficult problems surrounding earlier scholars’ misogynistic views of Heloise and the current tendency to reject psychologically-oriented studies as too subjective were reviewed. Mary McLaughlin, whose pioneering work on Abelard had, in the first place, inspired many present to enter this field of scholarship, clarified the important reasons why the letters remained unknown for so long and discussed other problems in historical methodology as well as the frustration of trying to understand the true feelings and motivations of this religious pair at such a distance and with limited data.

Clarissa Atkinson concluded the workshop with a review of the meaning of “Women’s Voices” in the context of Margery Kempe of England and Birgitta of Sweden. Much discussion had centered on the scholar’s difficulty in distinguishing the woman’s voice from that of her male scribe, but Clarissa raised the importance of taking into account a third party, “heavenly voices.” Accounts of women’s voices are actually often dialogical, i.e. dialogues between the woman and one or more heavenly voices such as with the Virgin Mary. Or “God commands her to speak.” In the case of Margery Kempe there are further aspects to her “voice,” some “disruptive voices”: the devil’s foul words; her inability to voice her confession; and her slander of her husband.

Clearly the word mystic is used far too loosely in the scholarship about women and the whole issue of women’s mysticism needs rethinking and careful use of source material.

The names and addresses of any of the scholars mentioned above can be obtained by writing to: Elizabeth Makowski, Columbia Women’s Studies Program, 763 Schermerhorn, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027 or phone (212) 854-3277.

Abbreviated Bibliography of Works by Mary Martin McLaughlin

2. “Survivors and Surrogates: Children and Parents in Western Society, Ninth to Thirteenth Centuries,” in The History of Childhood, ed. L. de Mause, The Psychohistory Press, New York, 1974 (also Harper Torchbooks, 1975), pp. 101-181.

3. “Peter Abelard and the Dignity of Women: Twelfth Century `Feminism’ in Theory and Practice,” Pierre Abelard, Pierre le Venerable: Les Courants philosophiques, litteraires et artistiques en Occident au milieu du XIIe siecle(Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, no. 546), Paris, 1975, pp. 287-333.

4. “Looking for Medieval Women: An Interim Report on the Project `Women’s Religious Life and Communities’,” Medieval Prosopography 8 (Spring 1987), 67-91.

5. “Creating and Recreating Communities of Women: The Case of Corpus Domini, Ferrera,” Signs 14 (no. 2, Winter 1989), 293-320. Also in Sisters and Workers in the Middle Ages, ed. Judith M. Bennet et al. (Chicago, 1989), 261-88.

6. The Portable Medieval Reader, New York, The Viking Press, 1949, revised ed., 1968 (with James Bruce Ross). (who, by the way, is also a woman scholar active from the 1950’s on [BR note]).

7. The Portable Renaissance Reader, New York, The Viking Press, 1953, revised ed., 1968 (with James Bruce Ross).

Sexual Miscommunication

I think it is fair to say that authors make the best abstracts of their own works. We owe it to Paul Watt to rectify our summation of his AAR panel paper delivered last November in New Orleans. He certainly did not suggest that “the kinds of sexual prohibitions attending Augustinian Christianity were analogous to developments in Japan with Pure Land Buddhism,” (IMJS REPORT, Vol. I, p. 6) but on the contrary, because of various factors in the Japan case, believes that Christians of an Augustinian persuasion and Japanese Pure Land followers did not regard sexuality in the same way. What he did say about Pure Land Buddhism and Augustinian Christianity was that neither believed that the human being had the power to do what people like Jiun argued they did — namely, overcome their weaknesses and shortcomings. Consequently, in terms of their views of society, both Augustinian Christianity and Pure Land Buddhism ended up accepting the status quo. Paul Watt’s consideration of views of the person and of the body are elaborated in his paper “Body and Society in Jiun’s (1718-1804) Buddhism,” which will appear in the research volume now being compiled by the “Women and Buddhism in Pre-Modern Japan” project.

Abstracts of the papers presented at the Mid-Atlantic Region of the American Academy of Religion meetings in New York on March 22 and again at the Assocation for Asian Studies meeting in New Orleans April 12 are herein supplied by the authors themselves. (see above)

— Barbara Ruch

[ Volume 2 of IMJS Reports was compiled by Indra Levy ]

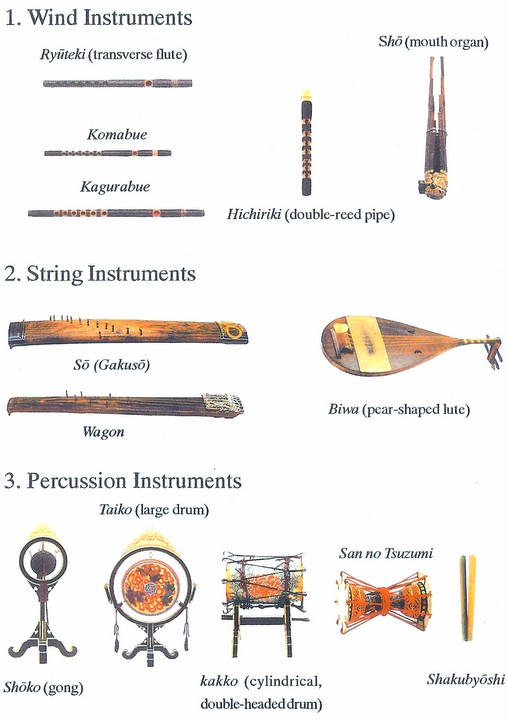

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.