IMJS: Japanese Cultural Heritage Initiatives

Columbia University

Treasuring the Past・Enriching the Present・Transforming the Future

- This event has passed.

30th Anniversary Event: International Symposium “The Culture of Convents in Japanese History”

Saturday, November 21, 1998 - Monday, November 23, 1998

国際シンポジウム『日本史の中の尼寺文化』

International Symposium: “The Culture of Convents in Japanese History”

![]() Since the 6th century royal women have played key roles in the establishment of Buddhism and the founding of monasteries and convents in Japan. They continued to do so during medieval times when Buddhism, combined with native Shinto beliefs, became virtually universal. Then, from the 13th century until the overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868, daughters of emperors and shoguns became the abbesses of an elite network of Buddhist convents that came to be known as monzeki amadera or imperial convents.

Since the 6th century royal women have played key roles in the establishment of Buddhism and the founding of monasteries and convents in Japan. They continued to do so during medieval times when Buddhism, combined with native Shinto beliefs, became virtually universal. Then, from the 13th century until the overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868, daughters of emperors and shoguns became the abbesses of an elite network of Buddhist convents that came to be known as monzeki amadera or imperial convents.

When these women took the tonsure and assumed leadership of these religious institutions, they brought with them, as if a dowry to a marriage, the highest cultural products of their age – superb furnishings, libraries of books, secular and religious scrolls, paintings, screens, lacquer ware, utensils for the spiritual disciplines of tea and flower arrangement, and multitudinous other works of art—so much so that these convents over the centuries became known as bikuni gosho or “nun’s palaces.” Once a woman took the tonsure, her magnificent secular robes remained treasures of the convent. If she had entered as a child, her exquisite toys and dolls, likewise, were treated with great care and preserved. In short, these convents are today like small, locked jewel boxes filled with the pearls and precious stones of historic data, somehow forgotten, waiting to be rediscovered.

In 1868 the Japanese government established a policy of separation between the Shinto and Buddhist faiths and banished Buddhism from the court. Royal women were forbidden to become Buddhist nuns, and these historical convents at once lost not only imperial and shogunal patronage but also an extraordinary pool of highly educated aristocratic women to serve as abbesses. Postwar land reform undermined their existence further by depriving the convents of the income-producing estates that had been willed to them by believers. Historically, they have had no “congregations” to rely upon.

In Japan, where culture is so carefully treasured, it is amazing to discover that these extraordinary, unique convents became the victim of 19th-century politics, were divested of imperial patronage, and as institutions for women, were ignored by male scholars. Yet the convents represent not only one of Japan’s most extraordinary historic monuments, but also institutions unique in all of world history. Today, each of these convents is a private temple-residence with only one or two nuns, and those with only tenuous ties to the former aristocracy. Unlike most famed monastery-temples for monks in Kyoto today, therefore, the imperial convents are not open to the public except on very rare occasions.

The women now who have decided to become Buddhist nuns and devote themselves to life careers in the imperial convents that have survived are vital spiritual and cultural guardians of one of the most extraordinary of institutions in Japanese history. Their challenge is to preserve the great treasures and traditions left to them by royal women of the past – and they must do so having been deprived, by dint of 19th-and 20th-century politics, of the intellectual and financial patronage of Japan’s elite. We are deeply grateful, therefore, for the privilege extended to the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies that has allowed us to begin to examine their great store of records and view the treasures of Japanese cultural history related to the generations of powerful women who became nuns there.

It was in 1993 that the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies became aware of the severely threatened state of these extraordinary temple-convents and was privileged to obtain the permission of the abbesses to begin to examine their great store of unstudied records and to view their treasures. The problems of photography and restoration proved to be extremely urgent. Her Majesty Empress Michiko learned of the Institute’s work and its severe financial constraints and in 1999 gave personal support to the work, enlisting as well the expertise and assistance of the eminent artist Ikuo Hirayama, head of the Foundation for Cultural Heritage.

With that Foundation’s support we began the delicate task of assisting the abbesses of the thirteen remaining imperial convents to preserve and restore their precious treasures.

In 2000 the World Monuments Fund of New York, which has worked for nearly four decades on over 400 important and imperiled works of art and architecture in over 80 countries, joined hands with us in support of the restoration of the convents’ historically unique architectural structures and gardens. On display in the Rotunda of Low Memorial Library are “before and after” photographs of our first architectural restoration, that of the Amida Chapel at Hōkyōji Imperial Convent, which was the private worship chapel of Hōkyōji’s abbess, Princess Kin no Miya, daughter of Emperor Kōkaku (1774-1840). Our long-term goal is to repair and restore all thirteen of the remaining imperial Buddhist convents, which are one of Japan’s rare “endangered species.”

Hōkyōji Imperial Convent

Hōkyōji convent traces its history back to its status as a tatchū or sub-temple, then called Fukuniji, belonging to the great temple-convent Keiaiji, which had been founded in the 13th century by the Rinzai Zen Abbess Mugai Nyodai. Keiaiji subsequently enjoyed a reputation as the highest-ranking “Five Mountain” Zen convent in medieval Kyoto. Fukuniji had fallen into disrepair in the 14th century and is believed to have been restored by Princess Karin no Miya, daughter of Emperor Kōgon (1313-1364), who had become the nun Egon there. A statue of the bodhisattva Kannon holding a mirror that had been caught up in fishing nets in Ise bay was donated to the convent, and as a result Egon renamed the convent Hōkyōji (Temple of the Treasured Mirror).

Hōkyōji subsequently had close ties to the Ashikaga shogunal house and was led by women from the shogunal family. From the 17th century on, however, beginning with the nun Kyūgon, daughter of Emperor Gomizuno’o, the position of abbess was held by a succession of imperial princesses. Although Keiaiji burned in the late medieval wars, many of its sub-temples preserved its treasures, and under Hōkyōji’s abbess Richū-ni, another daughter of Emperor Gomizuno’o, an upsurge in the veneration of Keiaiji, Abbess Mugai Nyodai occurred.

Hōkyōji houses many decorative court dolls as well as many toy dolls cherished by emperors, empresses and princesses. In spring and fall it holds a public exhibition of these treasured dolls and has gained the affectionate nickname “The Doll Temple” (Ningyō-dera). Every October it also holds an annual Buddhist funeral service for dolls that during the year have suffered fatal mishaps and are brought to the convent by their children-owners.

The convent is also famous for its flowering fruit trees, lawns of hair moss, and seasonal gardens unique to the convent. For a century and a half each abbess has gathered the seeds and hand-cultivated a rare variety of ribboned pinks that were presented to the convent by Emperor Kōkaku during the 18th century, and yearly they still bloom anew.

The World Monuments Fund has joined hands with the Institute so as to actualize the restoration of Japan’s thirteen remaining imperial convents whose existence, little known even in Japan, hovers on the edge of extinction. These world heritage historical treasures of architecture and gardens are cursed with the present-day dual burden of being, on the one hand, institutions by and for women and, on the other hand, having been politically and economically amputated by 19th-century government fiat from their imperial base.

The Amida Chapel at at Hōkyōji imperial convent was selected as a pilot architectural and interior restoration project in our partnership with World Monument Fund. This restoration, which was completed in August of 2003, is the first milestone in the journey to preserve these jewel-like treasures. We hope the reader of these words will help to fund us on this journey.

The Amida Imperial Chapel at Hōkyōji

It was the tradition of Japanese courts for many centuries not only to give over private villas to be dedicated as monastic temple convents, but in some cases, to have an entire building or a room dismantled from the imperial palace complex itself and to donate it to an existing temple-convent. It is sometimes referred to as a “Moving” Architectural Tradition. This symbolic relationship between court and convent means that in some cases historic rooms used by emperors or empresses in the palace can be viewed and appreciated now only in their present convent setting, since subsequent fires destroyed the palace itself.

This is true of the Amida Chapel at Hōkyōji. In 1847 this Imperial Chapel was installed in Hōkyōji, having been dismantled from its original location in the Imperial Palace, Kyoto. It was transferred to the convent under imperial order, the dying wish of Emperor Ninkō, whose sister, Princess Kin no miya had taken the tonsure at Hōkyōji as the nun Rikin. The Emperor’s Imperial Chapel became her private chapel. It houses an image of Amida that had been created by or commissioned by their father, Emperor Kōkaku (reigned 1779-1817), who was a devout practitioner of Buddhism. After his father’s death, Emperor Ninkō, likewise, a fervent believer, had worshipped before this image in his own private quarters of the palace until his death.

With Profound Gratitude

We announce the names of major funders of our Imperial Buddhist Convent Research and Restoration Projects

Her Majesty, Empress Michiko of Japan

and

(in alphabetical order)

Bussho gonenkai

The Freeman Foundation

Chief Abbot Keidō Fukushima

Kajima Corporation

Ms. Izumi Koishi

Kyoto Lions Club

Medieval Japanese Studies Foundation

Mr. Takashi Saitō

Shibunkaku Group

Shiseido Company, Ltd.

Shinji Shūmeikai

Shoyeido Corporation

Taiko Trading Company, Ltd.

Prof. Toshikazu Shiokawa

Ms. Shizuko Tani

Tides Foundation

Toraya Confectionery, Ltd.

Toshiba International Foundation for the Arts

The World Monuments Fund

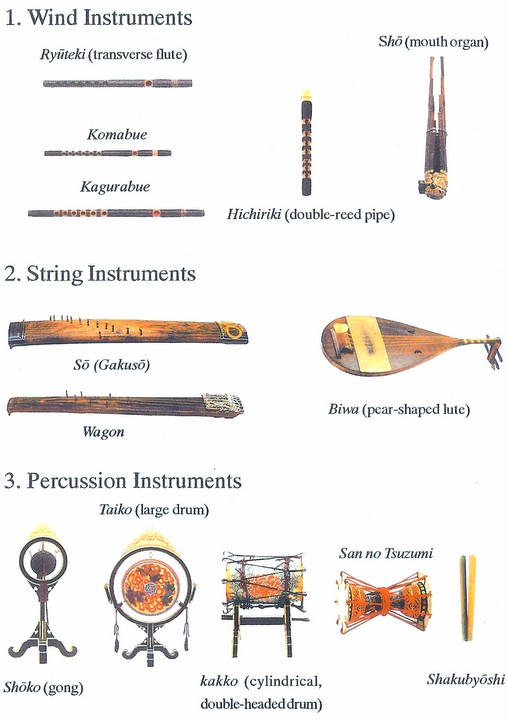

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.

In conjunction with the Gagaku-Hōgaku Classical Japanese Music Curriculum and Performance Program at Columbia University, launched in September 2006, the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies presents several public gagaku concerts and instrumental workshops to introduce the ancient music of Japan to a greater audience at Columbia University and in New York.